Science fiction has a respectable pedigree stretching from, by general agreement, Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, down through Jules Verne, H.G Wells and into the mid 20th century with Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke and others. It’s certainly a robust genre. And while that mid-century flourishing may be considered a golden age there are those who now think we are in a new golden age.

At the heart of this golden age is the Chinese writer, Cixin Liu. His fascinating and bewildering – in the best possible sense – science fiction will now be found occupying a sizable amount of space in the sci-fi sections of most bookshops. His voluminous imaginative works, replete with scientific, cosmological and astronomical detail, have been translated into more than twenty languages. His most famous, the epic trilogy entitled, Remembrance of Earth’s Past, has sold some eight million copies worldwide.

The timeline of the trilogy spans the present and into a time eighteen million years in the future. The London Review of Books has called the trilogy “one of the most ambitious works of science fiction ever written.”

The first part of the trilogy grapples with the threat to planet earth from a rival civilisation in our galaxy on a planet called Trisolaris. This is an ultra-advanced civilisation but its existence is jeopardised by the three-body problem. This is a problem in orbital mechanics which is caused by the unpredictable motion of three bodies under mutual gravitational pull. It is a classic problem first posed by Isaac

Newton. Cixin Liu wonderfully imagines the chaos this causes in the life of Trisolarans, ultimately provoking their plans to conquer and destroy the civilisation of our planet.

But Earth does temporarily cope with the threat, establishing a deterrent based on mutually assured destruction and forces the Trisolarans to share their technology. Sound familiar?

As the trilogy progresses, however, the threat from Trisolaris becomes a kind of side show and it emerges that a vast Dark Forest – volume two of the trilogy – of alien life is threatening the existence of all the universe’s civilisations. The denouement comes at the end of volume three, entitled Death’s End.

The profile of Cixin Liu expanded exponentially last year when Netflix launched its ten-episode series based on the first volume of the trilogy, The Three Body Problem. The second volume, The Dark Forest, is in production and will be streamed in 2026.

This event provoked a great deal of speculation about the geopolitical significance of the novel. Does Trisolaris stand for the United States and the threat it poses to the other global power of our age, China? Or vice-versa? Alternatively it might be read as a battle which might be envisaged between the technological giants of the 21st century. But a more interesting aspect of these three volumes, however, is what they reveal to us about the question of the existence of God within modern and supposedly atheistic Chinese culture.

Authors don’t like their work being reduced to simplistic interpretations, and Cixin Liu is no exception. “The whole point is to escape the real world!” he said, and not a commentary on history or current affairs. He says he just wants to tell a good story. He does that, but I also think he does more.

His story, despite what he says, does have some grounding in real events. The first volume features the horrific murder by the Red Guards of the father of the protagonist. Her reaction to this is central to the entire plot.

In another passage – in Death’s End – he would also have seemed to be sailing close to the wind in terms of a commentary on the history of his country.

The death sentence of a character deemed responsible for the pragmatic destruction of an outlying planet and its entire population is being debated. A discussion on the morality of capital punishment ensues. Is killing the perpetrator of such a crime morally acceptable? Someone asks:

“What about more than that? A few hundred thousand? The death penalty, right? Yet, those of you who know some history are starting to hesitate. What if he killed millions? I can guarantee you such a person would not be considered a murderer. Indeed, such a person may not even be thought to have broken any law. If you don’t believe me, just study history! Anyone who has killed millions is deemed à ‘great’ man, a hero.”

We might ask ourselves who he might have in mind?

A protagonist in the later part of the trilogy is a young scientist. She features in the entire story but really becomes pivotal in Death’s End and in its denouement. She represents the moral heart of the story.

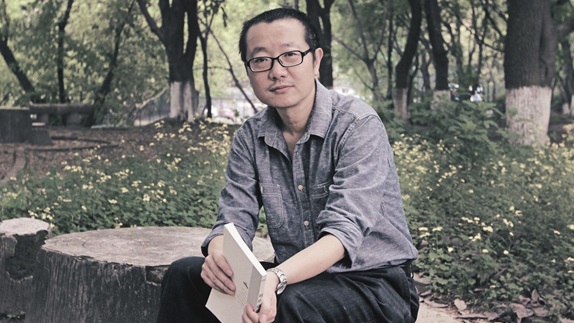

Jiayang Fan is a staff writer at The New Yorker. She met Cixin Liu (below) in Washington when he visited there for the presentation to him of the Arthur C. Clarke Award. Her interview with him was published in TNY’s print edition of 24th June 2019, with the headline “The War of the Worlds.” She describes an episode in the trilogy which depicts Earth on the verge of destruction.

A scientist named Cheng Xin encounters a gaggle of schoolchildren as she and an assistant prepare to flee the planet. The spaceship can accommodate the weight of only three of the children, and Cheng, who is the trilogy’s closest embodiment of Western liberal values, is paralyzed by the choice before her. Her assistant leaps into action, however, and poses three math problems. The three children who are quickest to answer correctly are ushered on board. Cheng stares at her assistant in horror, but the young woman says, “Don’t look at me like that. I gave them a chance. Competition is necessary for survival.”

In the story the crisis is averted and flight is no longer necessary. All the children survive.

The quotation underscores much of the moral dilemma portrayed in the trilogy. As Fan puts it,

In their pursuit of survival, men and women employ Machiavellian game theory and adopt a bleak consequentialism. In Liu’s fictional universe, idealism is fatal and kindness an exorbitant luxury. As one general says in the trilogy, “In a time of war, we can’t afford to be too scrupulous. Indeed, it is usually when people do not play by the rules of Realpolitik that the most lives are lost.”

Cheng repeatedly rejects such an ethic and persistently dodges all the actions which the roles chosen by her or imposed on her would have had lethal consequences for millions. Her sense of responsibility is her dominant characteristic. Near the end of Death’s End she composes what amounts to her apologia pro vita sua in which she writes, and which I quote without, I hope, spoiling anything:

Later, my responsibilities became more complicated: I wanted to endow humans with lightspeed wings, but I also had to thwart that goal to prevent a war…

And now, I’ve climbed to the apex of responsibility…

I want to tell all those who believe in God that I am not the Chosen One. I also want to tell all the atheists that I am not a history-maker. I am but an ordinary person. Unfortunately, I have not been able to walk the ordinary person’s path. My path is, in reality, the journey of a civilization.

This is the last reference to God in the books but it was not the first. Several key characters, professing atheism, in moments of great crisis say they wish they were not atheists.

Luo Ji got into the car quickly, not wanting Shi Qiang to see the tears in his eyes. Sitting there, he strove to etch the rearview-mirror image of Shi Qiang onto his mind, then set off on his final journey.

Maybe they would meet again someplace. The last time it had taken two centuries, so what would the separation be this time?

Like Zhang Beihai two centuries before, Luo Ji suddenly found himself hating that he was an atheist.

Another character’s response to the crisis she faces is as follows: “No, this can’t be happening,” Dongfang Yanxu said, her voice so low only she could hear it. It was for her own ears, in response to her earlier “god” exclamation. She had never believed in the existence of God, but now her prayers were real.

In another conversation between a group of scientists we find a character opting for Pascal’s wager to help him cope with the atheism which surrounds him.

“Doctor, do you believe in God?”

The suddenness of the question left Ringier momentarily speechless. “… God? That’s got a variety of meanings on multiple levels today, and I don’t know which you—”

“I believe, not because I have any proof, but because it’s relatively safe: If there really is a God, then it’s right to believe in him.

If there isn’t, then we don’t have anything to lose…”

Ringier mused, “If by ‘God’ you mean a force of justice in the universe that transcends everything—”

Fitzroy stopped him with a raised hand, as if the divine power of what they had just learned would be reduced if it were stated outright. “So believe, all of you. You can now start believing.” And then he made the sign of the cross.

At another point in the story, when a spaceship has gone off into outer space looking for and hoping to find a habitable planet, which the occupants fantasise as a new Garden of Eden. They are already experiencing a fatal sense of rivalry with another accompanying spacecraft. One of the occupants poses the question,

“Will what happened in the first Garden of Eden be repeated in the second?”

“I don’t know. At any rate, the vipers have come out. The snakes of the second Garden of Eden are even now climbing up people’s souls.”

Long-term hibernation, even for hundreds of years, is an option for scientists working on extended projects. Over the passage of years civilisation goes through periods of extreme decadence, provoked partly by a sense of hopelessness and desperation. In one sequence two central characters emerge from hibernation right into an orgy of licentiousness.

“Are those people?” Luo Ji asked in wonder.

“Naked people. It’s a tremendous sex party, with more than a hundred thousand people, and it’s still growing.”

Acceptance of heterosexual and homosexual relations in this era was far beyond anything Luo Ji had imagined, and some things were no longer considered remarkable. Still, the sight before them came as a shock to both of them. Luo Ji was reminded of the dissolute scene in the Bible before humanity received the Ten Commandments. A classic doomsday scenario.

“Why doesn’t the government put a stop to it?”

Shi Qiang asked sharply.

“How would we stop it? They’re completely within the law. If we take action, the government would be the one committing a crime.”

Shi Qiang let out a long sigh. “Yes, I know. In this age, police and the military can’t do much.”

The mayor said, “We’ve been through the law, and we haven’t found any provisions for coping with the present situation.”

It is not difficult to see a veiled reference by Cixin Liu to some of the mores which have developed in our own time.

In another climatic sequence, the same Luo Ji, one of the central protagonists in the novel is literally digging his own grave, into which he plans to throw himself and await death as doomsday seems to be approaching.

As Luo Ji worked to maintain a blank state in his mind, his scalp tightened, and he felt like an enormous hand had covered the entire sky overhead and was pressing down on him.

But then the giant hand slowly withdrew.

At a distance of twenty thousand kilometers from the surface, the deadly missile changed direction and headed directly toward the sun. The destruction of the planet was averted.

I cannot say that this is an intentional reference, but in the Bible you have this:

“Put forth thy hand from on high, take me out, and deliver me from many waters: from the hand of strange children:” (Psalm 143:7).

Finally, in Death’s End, when Cheng Xin is faced with a choice of accepting a mission critical for the survival of mankind, she is surrounded by crowds clamouring for her to accept the challenge.

She faced the crowd on the plaza. A hologram of her image floated above them like a colorful cloud. A young mother came up to Cheng Xin and handed her baby, only a few months old, to her. The baby giggled at her, and she held him close, touching her face to his smooth baby cheeks. Her heart melted, and she felt as if she were holding a whole world, a new world as lovely and fragile as the baby in her arms.

“Look, she’s like Saint Mary, the mother of Jesus!” the young mother called out to the crowd. She turned back to Cheng Xin and put her hands together. Tears flowed from her eyes. “Oh, beautiful, kind Madonna, protect this world! Do not let those bloodthirsty and savage men destroy all the beauty here.

(Correction: in paragraph four of this post, ‘solar system’ has been replaced by ‘galaxy’.)