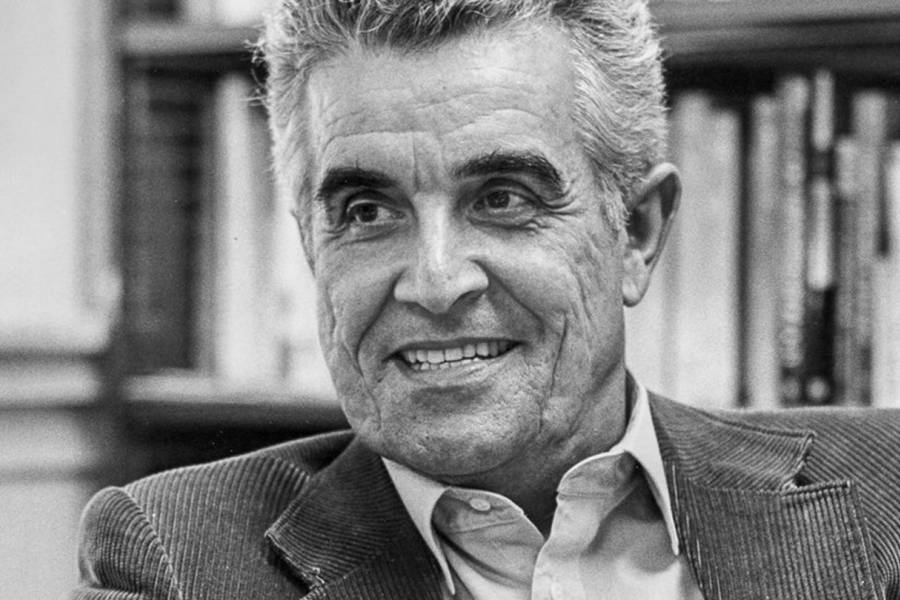

Back in the late 1950s and 1960s the film-maker Ingmar Bergman’s prestige and reputation were at their height. In those years anticipation of the next Bergman film to arrive in cinemas was akin to the anticipation today of the next film from Christopher Nolan or Terrence Malick. They were the works which dominated cultural conversation for months after their release. Why was that?

In a word I think we can say it was all about ‘meaning’ – man’s search for meaning, the mystery of human and divine love and the existence of God.

Bergman’s language, the visual language with which he explored this overriding universal theme, was full of symbolism. Indeed, even at that time, symbolism was so central in his language that some whose literacy was less developed, felt the symbolic imagery was somewhat overwrought. That was nonsense. Sadly, however, that illiteracy seems to have increased.

Pope Francis, in his Apostolic Letter of 2022, Disiderium desideravi, quoted Romano Guardini about the importance of liturgy as our path to God and the importance of symbols in liturgy. Guardini wrote of what he saw as “the first task of the work of liturgical formation: man must become once again capable of symbols.” The Pope pointed the finger at us all in this regard: “This is a responsibility for all, for ordained ministers and the faithful alike. The task is not easy because modern man has become illiterate, no longer capable of reading symbols; it is almost as if their existence is not even suspected.” Strong words.

Moving back to Bergman’s work, here are even stronger words from Lawrence Brooks – a disaffected figure in the Hollywood ecosystem:

“95% of film directors are so dumb that the very idea of including symbolism in their movies is beyond their capabilities.” Most film directors are just “trying to get the job done on time, on schedule. Messages & Symbolism in modern film? Ha! People like Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, Fincher, Nolan, and Kubrick are very rare indeed.”

Bergman’s three great early films, The Seventh Seal, The Virgin Spring and Through A Glass Darkly, even in their titles are all dependent on our capacity to read symbols if we are to have any chance of understanding what they are about. They are all deeply religious works. Much of his later work, while ultimately leading to questions of human fulfilment, are not explicitly religious. These are.

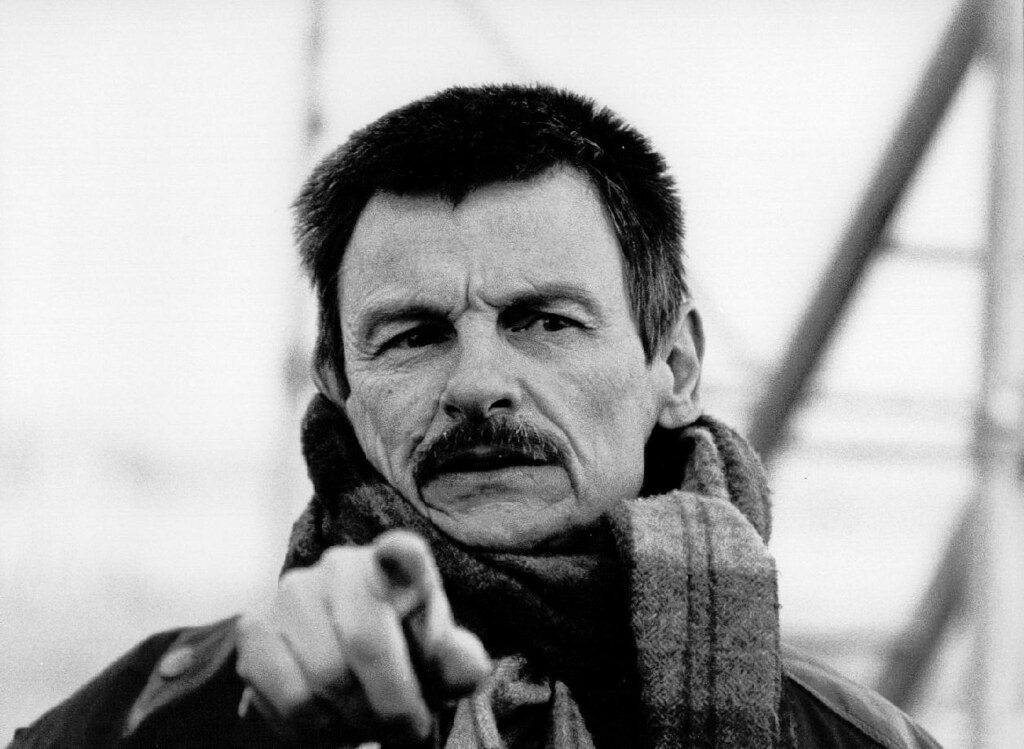

The Seventh Seal tells of the journey of a medieval knight (Max von Sydow) and a game of chess he plays with the personification of Death (Bengt Ekerot) who has come to take his life. In The Book of Revelation the Lamb breaks open seven seals. “And when the Lamb had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour.” The motif of silence refers to the “silence of God,”, the silence with which the knight is struggling and which is threatening to destroy his faith throughout the film.

The two powerful iconic images in the film are those of Death playing that game of chess with the knight – which continues at intervals throughout the film – and the final image of the Dance of Death. Both these images are visible today in two different churches in Sweden, both Lutheran but both formerly Catholic.

Another writer from the Hollywood ecosystem, Rick Manly of the University of California, wrote of this film, “With its images and reflections upon death and the meaning of life, The Seventh Seal had a symbolism that was immediately comprehensible to people trained in literary culture who were just beginning to discover the ‘art’ of film, and it quickly became a staple of high school and college literature courses.”

British cultural broadcaster, Melvyn Bragg, wrote of Bergman’s work: “It is constructed like an argument. It is a story told as a sermon might be delivered: an allegory…each scene is at once so simple and so charged and layered that it catches us again and again…Somehow all of Bergman’s own past, that of his father, that of his reading and doing and seeing, that of his Swedish culture, of his political burning and religious melancholy, poured into a series of pictures which carry that swell of contributions and contradictions so effortlessly that you could tell the story to a child, publish it as a storybook of photographs and yet know that the deepest questions of religion and the most mysterious revelation of simply being alive are both addressed.”

Benjamin Ramm is a journalist who writes for the BBC and other media. He argues that It’s not right that Bergman is always described as dark and gloomy. He was a deeply humane artist with great empathy. Bergman’s primary theme, he says, is not death but the redemptive possibility of love.

F. B. Myer, a Baptist pastor, writing in light of World War I and the sufferings and sorrows that many endured during that time, refers to death as a sister and the enduring comfort and strength that God provides throughout the trials which may accompany it. The shrouded figure accompanying our protagonist throughout The Seventh Seal is spoken of as the personification of Death. In fact we realise at the very end of the film, as the young girl who had been rescued from a vicious attacker, looks and smiles at the face of the shrouded figure, that she is looking at the face of her Redeemer. What in fact is Death but a manifestation in our lives of the Providence of God? The dancing company of pilgrims silhouetted against the sky, following this figure, are on their way to eternity. All of them are people who have struggled against adversity of one kind or another. They are all good people now dancing to their eternal reward.

Another rich vein of symbolism in The Seventh Seal is seen in the figures of Jof and Mia with their infant child. The knight appears to shield them and let them go off unharmed by his shadowy chess opponent whom he assumes wants to harm them. Read it as you wish but his opponent is not taken in by the tossed-over chess board. He is aware of a greater mission to the world of of which this family is a symbol.

The Seventh Seal is an immortal work which ranks as one of the greatest achievements which the art of cinema has left us. It ranks in its own canon as Bach’s Mass in B Minor ranks in the musical canon.

In Benjamin Ramm’s view, what makes Bergman radical is his unfashionable sincerity.

“In over 60 films in a career spanning six decades, Bergman charted the harrowing cost of what he called ‘emotional poverty’. His work in all its variety is arrayed against the cynical, clinical, calculating, careless, and callous; he decries our lack of compassion and our “empty but clever” irony. What makes Bergman radical in our own era is his unfashionable sincerity, which leaves him open to mockery and parody”

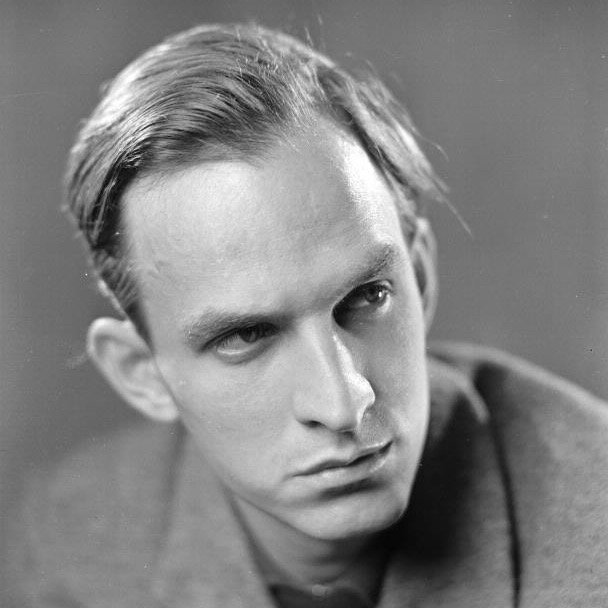

Two other films, The Virgin Spring (1960) and Through a Glass Darkly (1961), both of which received Academy Awards, along with The Seventh Seal, constitute a kind of ‘faith trilogy’ in Bergman’ s work . The title of the 1961 film is a reference to St Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians (13.12).

The Virgin Spring is set in medieval Sweden, It is a tale about a father’s merciless murder of two men and an innocent child implicated in the rape and murder of his young daughter. The story was adapted from a 13th century Swedish ballad well-known throughout Scandinavia. But it is not just a revenge tale. It is the story of the father’s response to a miracle on the site of his daughter’s murder in which a spring gushes forth from the dry forest earth. The father falls on his knees and asks God’s forgiveness for his own vengeful and sinful crime of murder. Bergman was himself a troubled soul – but then so was King David.

Through a Glass Darkly is a story, in a modern setting, about a troubled family group in which the daughter, Karin is suffering from intermittent symptoms of schizophrenia. Meanwhile (spoiler) her brother Minus is at emotional odds with his father, David. They seem not to be able to talk to each other. They are living on an isolated island and when Karin has a relapse she is taken off by helicopter to receive medical attention. At that point father and son help each other and Minus tells his father that he is afraid that he also may be losing his grip on reality. He asks his father if he can survive that way. David tells him he can if he has “something to hold on to”. He tells Minus of his own hope: love. David and his son, quoting Sacred Scripture, discuss the concept of love as it relates to God. They find solace in the idea that their own love may help sustain Karin. The ice is broken and Minus is exultant that he finally had a real conversation with his father.

Bergman was not entirely happy that he had achieved his artistic and religious objective with this ending. He felt he had not fully expressed the truth he wanted to convey and that the optimistic epilogue was “tacked loosely onto the end,” causing him to feel “ill at ease” when later confronted with it. He added that “I was touching on a divine concept that is real, but then smeared a diffuse veneer of love all over it.”

Through a Glass Darkly is a more complex story than the other two and while rich in symbolism is also influenced by neo-realism. Despite his reservations It is profoundly moving. Among Bergman’s 60+ films it ranks as one of his definitive masterpieces.