Christians truly are at a head-scratching moment as they confront the drift of the modern secular world. Drift indeed may be a too gentle a phenomenon to describe what is bearing down on them. It is much more like a deluge and so much so that not a few of them must be contemplating building an Ark. They have wished for better for this world, have worked for its configuration to a model of our species’ true nature but now appear to have their backs against the wall. They continue living in this secular society hoping for peaceful coexistence with those who do not see our nature or our world in the same way as they do. With each day that passes this hope is challenged more and more.

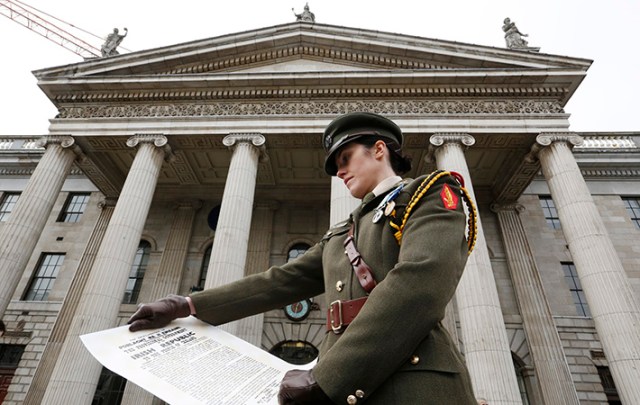

For decades now there has been concern and debate among believing and conscientious Christians about their representation in the legislative assemblies of the Western world. In jurisdictions stretching from the United Kingdom, through Ireland, France and Spain to the United States and Canada, national and federal chambers have one by one enshrined laws which contravene central moral principles of their faith.

These legislatures have now set out on a path to recalibrate their respective societies according to the fundamental principles of an anthropology alien to much of what Christians both rationally and religiously know and believe to represent the true nature of the human species.Today the political establishment seems to be turning its back on the Christian ethics which for 1700 years have been advancing as the standard behind our laws.

But this is not really their biggest problem. The first Christian communities on the planet lived under such regimes, managing a level of coexistence which enabled them to survive, thrive and evangelise – barring sporadic episodes of paranoid persecution. The forces which from time to time set out to destroy them were for the most part inept and dysfunctional. The Edict of Milan in 313 brought the political establishment to its senses and outlawed intolerance against Christians.

Now in the 21st century, through a creeping process in the legislatures of formerly Christian countries across the globe, the notional Edict of Milan has been revoked and the right of Christians to practice and live by the principles of their religion is now no longer being tolerated. This, of course, has happened before, but never in a way in which it is happening now.

Within a few decades of the death of the Emperor Constantine, his successor, Julian, tried to reverse the Edict. For that abortive attempt he is known in history as Julian the Apostate. Then came the armies of Islam which wiped out Christianity in half the known world, and threatened to do so in the other half. Nearer to our own time the French Revolution sent thousands of Christians to their deaths. Then in the last century the twin scourges of Marxism and Nazi ideology did the same.

On all those occasions the challenge was met and the threat subsided.

But now it is different. In our age there is a new element. It would seem that the grass roots have been to a degree, transformed. Add to this the sad trend among the political classes of abandoning any pretension to leadership. They seem to be followers of fashion and are now turning their backs on Christian values because that is the way they think the wind is blowing. They unashamedly leave their consciences at the door when they enter legislative assemblies. Christians are being regularly told now that they are on the wrong side of history.

The character of the modern state compounds the problem for Christians. In 313 the Roman Empire may have covered the lion’s share of the known world. Despite, however, the impression of power it has left us with, its totalitarian reach was minuscule in comparison with the reach modern governments have into our lives. We tolerate this totalitarianism because it is accepted as democratic – up to a point – and is seen to be “in our best interests”.

Is it either? This is now the question that is preoccupying many of us, Christians or not. This question takes us away beyond the Christian-secular debate. Nevertheless, the essential issue, which many see affecting our lives, is at the heart of the predicament of the Christian in the modern 21st century world. A tyrannical populism, driven by ambiguously democratic forces, now seems rampant in the public square. A formerly benign Leviathan, called up to help secure the common good, has now gone native. The threat he poses to the believing Christian is exemplified in the news this week – reported in Time magazine and elsewhere – about big business’ latest foray into the culture wars. Time tells us:

Disney says it will not film in the state of Georgia if a bill, which critics say would effectively legalize discrimination based on sexual preferences, becomes law. Gov. Nathan Deal has until May 3 to sign or veto the Free Exercise Protection Act, which protects faith-based organizations that refuse to provide services that would violate their beliefs—such as performing gay marriages, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Add to this what we remember of the relentless drive of big media and internet corporations which successfully pushed the political establishment to legalise same-sex marriage over the past few years and we have every right to ask what has happened to the democratic process.

The answer may be simple. These unelected corporations in their turn, like the politicians, are responding to a populist new reading of the nature of our species. They are driven by the market and they are reading the bottom line – follow the money.

Christians look on in dismay as all this unfolds. Not only are their values being disregarded. Their personal freedom, their freedom of association and their freedom of conscience is being threatened and increasingly denied. The consciences of the Little Sisters of the Poor, the future of the work they undertook to dedicate their lives to for the love of their God and the good of mankind is now in the hands and at the mercy of eight judges of the US Supreme Court. Should the Court decide in their favour – and I wouldn’t want to bet on it – there will be outrage and cries for their blood.

What Christians see before them is a population subverted by a reading of our nature which distorts and destroys what they see as some of the most precious truths about humanity. Not only has that happened but that same popular will is now seeking to tyrannically impose that vision of humanity on all. Coexistence is not on offer – and it is not just being denied by Disney.

What Christians are now asking is where did this reading of our nature come from? How did it take hold? German author Gabriele Kuby asks all these questions in her book, The Global Sexual Revolution: Destruction of Freedom in the Name of Freedom – now translated into English. In summary, her argument is this:

The core of the global cultural revolution is the deliberate confusion of sexual norms. It is the culmination of a metaphysical revolution as well–a shifting of the fundamental ground upon which we stand and build a culture, even a civilization. Instead of desire being subjected to natural, social, moral, and transcendent orders, the identity of man and woman is dissolved, and free rein given to the maximum fulfilment of polymorphous urges, with no ultimate purpose or meaning.

Kuby surveys gender ideology and LGBT demands, the devastating effects of pornography and sex-education, attacks on freedom of speech and religion, the corruption of language, and much more. From the movement’s trailblazers to the post-Obergefell landscape, she documents in meticulous detail how the tentacles of a budding totalitarian regime are slowly gripping the world in an insidious stranglehold. Here on full display are the re-education techniques of the new permanent revolution, which has migrated from politics and economics to sex.

Kuby’s work advocates one viable response, not just for the Christian, but for all interested in the true good of humanity. It is essentially a call to action for all to redouble their efforts to preserve freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and in particular the freedom of parents to educate their children according to their own beliefs, so that the family may endure as the foundation upon which any healthy society is built.

And where does all this leave the ordinary Christian who conscientiously wants to live and practice the mandate he or she considers they have received from Christ and which is summarised neatly in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, (900):

Since, like all the faithful, lay Christians are entrusted by God with the apostolate by virtue of their Baptism and Confirmation, they have the right and duty, individually or grouped in associations, to work so that the divine message of salvation may be known and accepted by all men throughout the earth. This duty is the more pressing when it is only through them that men can hear the Gospel and know Christ. Their activity in ecclesial communities is so necessary that, for the most part, the apostolate of the pastors cannot be fully effective without it.

The chances are it will leave them in prison. Kuby’s book enumerates more than one case where it has done so.

But Christian culture is not dead, or even dying. It is taking stock and – although wrong responses are never off the option list which may be presented for action – it will survive and thrive.

From the earliest days of the history of their Faith, the Christian community was assailed by opposing forces, from within as well as from without. It will never, it seems, be otherwise. Each struggle in which they have had to engage has presented new challenges, new issues and new dangers, or at least new variations on old dangers. On every occasion solutions have been hammered out and victory has lead it to new and even richer landscapes. Believing Christians may have to scratch their heads a little more but they do not doubt that they will also prevail in the struggles they face today.

(Updated on 26 March with the following sentence from the original draft. It is in the third paragraph and was inadvertently committed from the first posting: Today the political establishment seems to be turning its back on the Christian ethics which for 1700 years have been advancing as the standard behind our laws. )