“No English novelist has explored man’s soul as deeply as Dostoevsky”, E. M Forster wrote in his wise little book, Aspects of the Novel.” Forster’s viewpoint was not much appreciated by some of his fellow countrymen. But he made no apologies for it. Any claim to the contrary was for him simply a mark of provincialism.

Describing Dostoevsky, Forster said, “He has penetrated-more deeply, perhaps than any English writer – into the darkness and goodness of the human soul, but he has penetrated by a way we cannot follow. He has his own psychological method and marvellous it is. But it is not ours.”

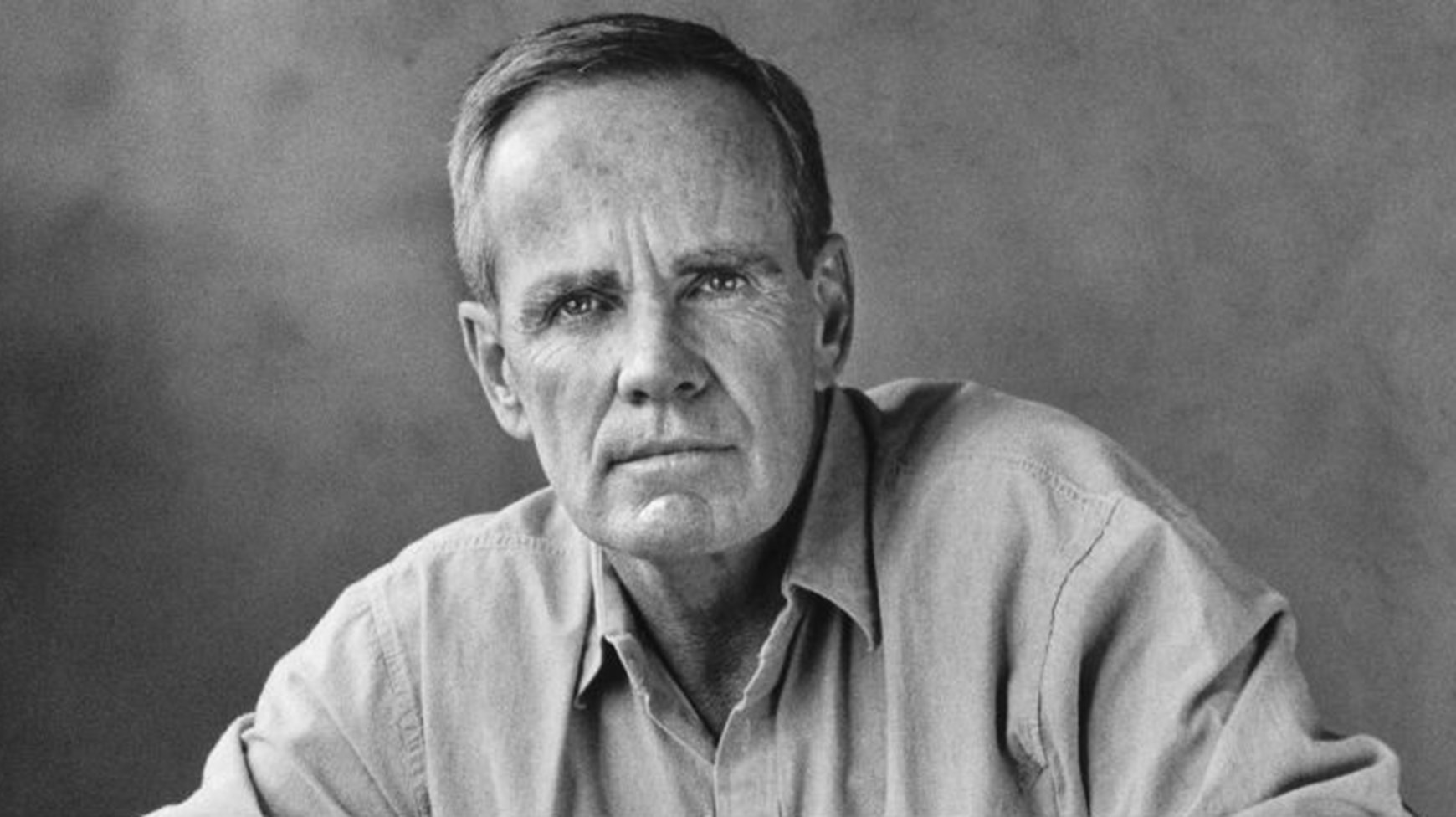

But there may be another novelist in the English language who now comes close to Dostoevsky in his searing power to expose the darkness into which our kind can enter and destroy ourselves. This is the Irish-American Cormac McCarthy, described by many now as the greatest American novelist of the late twentieth century.

Dostoevsky’s work is looked on by many as prophetic and in no novel is he more so that in his late masterpiece, Demons (also published under the titles The Possessed and The Devils). He did not live to see the Russian Revolution nor the horrors which it and its ideology brought to the world. But in Demons he described its roots and had no doubt that if those roots bore their bitter fruit, a human catastrophe would be the outcome. He was right, but he also knew that those roots had one primal origin, a demonic one.

One hundred years after Dostoevsky published Demons, Cormac McCarthy published what many consider to be his masterpiece, Blood Meridian. It is as dark and forbidding as Demons, and like that book is also rooted in actual records of man’s inhumanity to man. Furthermore, there is no question but that it can be interpreted as a record of demonic possession. Read in conjunction with the body of McCarthy’s work, especially Outer Dark, No Country for Old Men and The Road, one cannot but see that McCarthy’s preoccupations – never explicitly stated, but always lurking in the dark shadows of his work – are very similar to Dostoyevsky’s. Even central characters in Blood Meridianmight be read as reinterpretations of those in Demons.

In Demons, the “possession” described affects not one man or a few families, but an entire provincial town and all levels of its society. However the two central and tragically evil characters are Nicolai Stavrogin and Pyotr Verkhovensky. They embody much of the preternatural demonic character of McCarthy’s “Judge” Holden in Blood Meridian. The hapless victim of the calculated vindictive cruelty of Pyotr Verkhovensky, would-be but reluctant student revolutionary, Ivan Shatov, in some way is mirrored by the equally hapless “Kid” in McCarthy’s novel.

For much of the journey which Blood Meridian takes us on we are accompanying a murderous gang of US renegades – in which “Judge” Holden is the second in command – on a mission to exterminate native Americans south of the Mexican border. The smell of evil is palpable. A newspaper account of the historical personage on which McCarthy based his character, the “Judge”, reads as follows:

His desires was [sic] blood and women, and terrible stories were circulated in camp of horrid crimes committed by him when bearing another name, in the Cherokee nation and Texas; and before we left Frontereras a little girl of ten years was found in the chaparral violated and murdered. The mark of a huge hand on her little throat pointed him out as the ravisher as no other man had such a hand, but though all suspected, no one charged him with the crime.

In Demons, Nicolai Stavrogin, whose sensual brutality is mirrored in “Judge” Holden,has a similar catalogue of evil deeds on his record and in the end is driven to suicide with little other explanation for it than a demonic one. The cold and cruel ideology of Pyotr Verkhovensky is mirrored in the other side of Holden.

We hesitate, understandably, to preoccupy ourselves too much with the Evil One. Nevertheless, our Lenten season begins with an account of Christ’s encounter with Satan in the desert in the forty days he spent there before his public life began. Our failure to acknowledge the perpetual existence of the father of lies may be a dangerous habit of our age which considers the material world as the only real world.

One is reminded of the teaching of Joseph Ratzinger when he asked us to reflect on this:

Have not we also thought that spiritual realities are less real than the material? Is there not also a tendency to defer announcing the truth of God in order to do “more necessary” things first? In fact, however, we see that economic development without spiritual development is destroying man and the world. (Journey to Easter).

Denis Donoghue, probably the most learned literary critic Ireland has ever produced, when teaching Blood Meridian to his students in the University of New York, recalled the words of another famous critic, Lionel Trilling, when he spoke of the “bitter line of hostility to civilisation” that runs through modern literature. Donoghue, however, does not bunch McCarthy’s work in that negative category, even though he appears to refuse to adjudicate any deed in his fiction (The Practice of Reading).

Donoghue writes, and taught his students, that while Blood Meridian appears to give privilege to primal, nonethical energies, and seems to endorse Nietzsche’s claim that art rather than ethics constitutes the essential metaphysical activity of man, McCarthy is not in fact endorsing that philosophy. Nietzsche, he points out, is “Judge” Holden’s philosopher, not McCarthy’s.

Donoghue admits that the experience of reading Blood Meridian is likely to be, for most of us, peculiarly intense and yet wayward. The book demands that we imagine forces in the world and in ourselves which we might think we have outgrown. He concludes, “We have not outgrown them, the book challenges us to admit. These forces are primordial and unregenerate, they have not been assimilated to the consensus of modern culture or to the forms of dissent which that consensus recognizes and to some extent accepts. They are outside the law.”

That is, I think, outside the law as our world knows law. Human law is a flawed edifice. The truth is that those forces are more real than we want to admit. At the end of the novel the “Judge”, before crushing the Kid to death in his monstrous embrace – although that death is not explicitly stated – has this conversation with his victim with this Nietzschean rebuke:

You came forward, he said, to take part in a work. But you were a witness against yourself. You sat in judgment on your own deeds. You put your own allowances before the judgments of history and you broke with the body of which you were pledged a part and poisoned it in all its enterprise.

Hear me, man. I spoke in the desert for you and you only and you turned a deaf ear to me… For it was required of no man to give more than he possessed nor was any man’s share compared to another’s.

Only each was called upon to empty out his heart into the common and one did not.

This, Donoghue says, “is the gist of the judge’s complaint against the Kid: he should have voided in himself every scruple, every impulse of kinship with the defeated, He should have retained no will but the common will, so far as that was embodied in the work of war and killing.”

Those words might well have been spoken by Pyotr Verkhovensky to Ivan Shatov in Demons prior to Shatov’s murder. Verkhovensky’s hatred of Shatov was personal but he hid it under the fiction that Shatov would denounce his revolutionary cell. The members of that cell, however, were not fooled, Dostoevsky’s narrator tells us; they knew that Pyotr Stepanovich was playing with them like pawns. They felt they had suddenly been caught like flies in the web of a huge spider; they were angry but quaking with fear. But that did not make them back away from their evil plan. Shatov’s fate was sealed.

With a resonance of Judas’ betrayal of Christ, Verkhovensky warns his accomplices, “Only just let anyone try slipping away now! None of you has the right to abandon the cause! You can go and kiss him if you like, but you have no right to betray the common cause. Only swine…act like that!” An allusion to the Gerasene demoniac whose demons ended up in the herd of swine.

It is at the scene of Shatov’s murder, after the deed is done, that the demon possessing one of the accomplices manifests himself openly, and in a way which is echoed in the murder of the Kid in Blood Meridian.

Lyamshin hid behind Virginsky, only peeping out warily from behind him every now and then, and hiding again at once. But when the stones were tied on and Pyotr Stepanovich stood up, Virginsky suddenly started quivering all over, clasped his hands, and cried fully at the top of his voice: “This is not it, this is not it! No, this is not it at all!”

He might have added something more to his so belated exclamation, but Lyamshin did not let him finish: suddenly, and with all his might, he clasped him and squeezed him from behind and let out some sort of incredible shriek. There are strong moments of fear, for instance, when a man will suddenly cry out in a voice not his own, but such as one could not even have supposed him to have before then, and the effect is sometimes even quite frightful. Lyamshin cried not with a human but with some sort of animal voice.

Squeezing Virginsky from behind harder and harder with his arms, in a convulsive fit, he went on shrieking without stop or pause, his eyes goggling at them all, and his mouth opened exceedingly wide, while his feet rapidly stamped the ground as if beating out a drum roll on it. Virginsky got so scared that he cried out like a madman himself and tried to tear free of Lyamshin’s grip in some sort of frenzy, so viciously that one even could not have expected it of Virginsky, scratching and punching him as well he was able to reach behind him with his arms.

Erkel finally helped him to tear Lyamshin off. But when, in fear, Virginsky sprang about ten steps away, Lyamshin, seeing Pyotr Stepanovich, suddenly screamed again and rushed at him. Stumbling over the corpse, he fell across it onto Pyotr Stepanovich and now clenched him so tightly in his embrace, pressing his head against his chest, that for the first moment Pyotr Stepanovich, Tolkachenko, and Liputin were almost unable to do anything.

Pyotr Stepanovich yelled, swore, beat him on the head with his fists. Finally, having somehow torn himself free, he snatched out the revolver and pointed it straight into the open mouth of the still screaming Lyamshin, whom Tolkachenko, Erkel, and Liputin had already seized firmly by the arms; but Lyamshin went on shrieking even in spite of the revolver. Finally, Erkel somehow bunched up his foulard and stuffed it deftly into his mouth, and thus the shouting ceased. “This is very strange,” Pyotr Stepanovich said, studying the madman in alarmed astonishment.

He was visibly struck.

“I had quite a different idea of him,” he added pensively.

He simply did not recognise, blinded by his own demonic-nurtured atheism, the nature of the monster which had confronted him. That was his first direct encounter with the Devil that evening. The next – I’ll spare you the detail – was with Kirillov, the atheist who wanted to be God and whom Verkhovensky was complicit in seducing to commit suicide. The account of his death and the diabolical manifestations which accompanied it has been described as “the most harrowing scene in all fiction”.

McCarthy’s fiction, as Donoghue says, makes no explicit adjudication on the evil deeds his characters perpetrate. That he leaves to us But in the character of the Kid we have an image of innocence lurking in the shadows and which the “Judge” realises he has failed to corrupt. Dostoevsky is much more explicit about redemption. One of the wonderful passages of the book is the deathbed conversion of Pyotr Verkhovensky’s father, Stepan Trofimovich.

Richard Pevear, one of Dostoevsky’s recent translators, comments in his introduction to Demons:

Here, in what many consider the darkest of his novels, Dostoevsky inscribes the fundamental freedom of Judeo-Christian revelation: the freedom to turn from evil, the freedom to repent. His vision is not Manichaean; he does not see evil as co-eternal with good. Evil cannot be the essence of any living person. The “possessed” can at any moment be rid of their demons, which are wicked but also false. The devil is a liar and the father of lies. And the lie here is the same as in the beginning: “you will be like God”.

One can only hope that the fracturing character of our own civilisation, penetrated as it has been again by a new Marxism, which we are rather naively branding with the silly label of “Wokeism”, is not the unfolding of a prophecy of the dehumanisation of our society as Dostoevsky’s was for Russian society at the turn into the twentieth century.

This article first appeared in the April, 2023, issue of the review, Position Papers.