Part Two

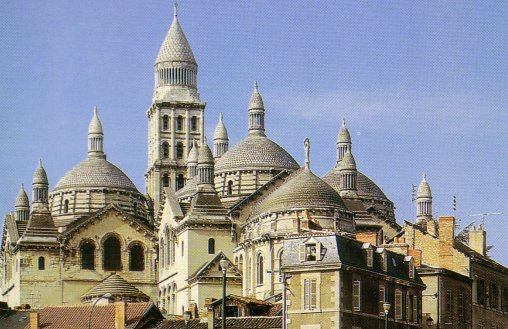

In August 1919 Eliot was still battling with the ideas and the form that would become The Waste Land. In that month he went, with Ezra Pound, on a walking tour of Provence. At one point they separated, Pound leaving to meet his wife. At this stage Eliot made what Matthew Hollis describes in his 2022 book on The Waste Land as a “his defining visit to Périgueux cathedral”. Hollis continues by saying that no account of what happened there is available but that “what is known is that what took place at the cathedral would be a turning point in Eliot’s life”.

The cathedral was dedicated to the legendary St Front, sent by St Peter to preach in the lands of Aquitaine. It was its later history which moved Eliot in some way, perhaps through the example of the powerful convictions of the protagonists of a later story. Provence and Aquitaine became battlegrounds in which Christianity had to confront two separate heresies in different ages, Arianism in one age and Albigensianism in another.

Bishop Paternus had been deposed as the Bishop of Périgueux in 361 AD for preaching Arianism, the heresy which held that Jesus was not truly the Son of God, and unequal to Him. Paternus, was fiercely punished by St Hilary of Poitiers, known as the “Hammer of Arians”. Hilary proclaimed that to deny the Trinity was not only folly, but a heresy. In substance Hilary said: To undertake such a thing is to embark upon the boundless, to dare the incomprehensible; to attempt to speak of God with more refinement than He has provided us with; it is enough that He has given His nature through the Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. “Whatever is sought over and above this is beyond the meaning of words, beyond the limits of perception, beyond the embrace of understanding.”

Hilary was writing in the fourth century but his language would resonate in Eliot in the twentieth. Eliot now found himself rudderless. It would be more than twenty years until his belief in the Blessed Trinity would flower definitively in Four Quartets. But in the early 1920s he still had many miles to travel. Nevertheless, these early Christian struggles shattered what was left of Eliot’s Unitarian foundations.

Hollis writes:

In Périgueux, that summer, Eliot was a son separated from the love of a father in death and in life, and had yet to find the guidance of a holy spirit with which his joining of the Church of England in 1927 would allow him to commune. In the chronicles of the building before him, and in his walking conversations with Pound, Eliot could trace the accounts of martyrs and heretics alike who had gone into exile – or gone into the fire – for their convictions or their sins, people who had found a measure to live by and even to die for, who had found a family of higher calling. What had Eliot to offer compared to such commitment? Not the “one great tragedy” of the war in which he was denied a part. Not the daily negotiations at the bank for a treaty that he considered immoral and unjust, and altogether “a bad peace”. Not the wedding vows, taken before God, that seemed to him to have turned to ashes in his hands. He found he had no ideological framework from which to respond. The Unitarianism of his childhood seemed to him a poor man’s fuddle: a culture of humanitarianism, of ethical mind games rather than a passionate adherence to Incarnation, Heaven and Hell… And in the absence of a religious conviction, his writing simply could not bear the weight: regarded merely for its satire and wit, it had yet to find the ground from which to respond to the intensity of the emotions he was experiencing.

Eliot now felt alone. Pound was a kind of Confucian and this meant nothing to Eliot. “There are moments,” wrote Eliot in 1935, “perhaps not known to everyone, when a man may be nearly crushed by the terrible awareness of his isolation from every other human being.” But this religious anxiety filling him at times with a sense of dispossession, of emptiness, turned out in fact to be cathartic, his dark night of the soul.

Hollis interprets it this way: “a dispossession was also an exorcism: a word to describe the purging of demons, as applied by the Catholic Church from as early as its second century: it is a removal of the bad by the good. But that wasn’t exactly what Eliot had said. A dispossession not of the dead but by the dead: not an action undertaken by him, but one done to him.”

He was now experiencing intimations of Purgatory, something alien to the theology of Unitarianism but surely something which might have remained in his subconscious from Annie Dunn’s prayers for the souls she believed to be in that place for a time. Hollis comments:

What transfixed Eliot in this moment was not heaven and hell, but purgatory, the temporary suffering or expiation for the purpose of spiritual cleansing. “In purgatory the torment of flame is deliberately and consciously accepted by the penitent,” Eliot wrote in his 1929 Dante. He made his own translation of the moment in the Purgatorio in which Dante is approached by souls from the flames: “Then certain of them made towards me, so far as they could, but ever watchful not to come so far that they should not be in the fire. The souls in purgatory suffer “because they wish to suffer, for purgation”, he wrote, because they wish to be in the fire, because “in their suffering is hope”.

In such a moment of isolation, Hollis notes, Eliot would write in years to come, he felt only pity for the man who found himself alone, as he had, “alone with himself and his meanness and futility, alone without God”. Even later he wrote that to be without the company of God is to be abandoned to the wilderness, to an endless seesaw between anarchy and tyranny: “a seesaw which in the secular world, I believe, has no end”.

Eliot’s The Waste Land was, in a way, a journey through Purgatory. Indeed its power to this day may ultimately rest on its character as a grim but hopeful reminder of this supernatural reality believed in by Christians and Jewish people. The Scriptural basis for the Christian belief in Purgatory is the instruction of Judas Maccabeus to his soldiers to pray for the souls of their dead companions.

The three last words of The Waste Land, one word repeated three times in fact, are Shantih shantih shantih. Eliot’s note on this tells us that repeated as here, they are a formal ending to an Upanishad. He adds a translation, “The peace which passeth understanding”, but says that this is “a feeble translation of the content of this word.”

Eliot’s great poem was soon recognised as a masterpiece of the modern world. Eliot took a few more years to reach his shantih in the Christian faith. He did reach it and from that vantage gave English literature more than one magnificent literary work which reflected the spirit of his now Christian soul.