Christopher Nolan has described it as the greatest war film ever made. I have not seen or read any elaboration by him of that opinion. It is not necessary. Not only isThe Thin Red Line a searing depiction of war, it penetrates to the heart of the struggle that is endemic in life itself.

One of the people who worked with him in the long process of making the film, Penny Allen has said of Terrence Malick’s oeuvre,

Terry’s work is all about the struggle for life. The fact that it’s a war film for me is only that it’s a metaphor for this and, in an odd way, I feel it’s true of all his films. He never judges people, as if there is nothing in Terry that is about existing morality in the conventional sense; it’s about man’s need for the spirit.

John Toll, his cinema photographer, said

As much as any film I’ve ever worked on, this picture was about an idea. I believe that what Terry wanted the film to be about, most of all, was that the real enemy in war is the war itself. War – not necessarily one side or the other – is the great evil. It isn’t often that one gets to work on films of this nature, and I’m grateful that I had the opportunity to participate in it.

There are two quotations, one from literature and the other from folklore which embody the phrase which gives the book by James Jones and Malick’s film its title. One is Rudyard Kiplings story Tommy, depicting the expendable private soldier fate in war:

Then it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ “Tommy, ‘ow’s yer soul?”

But it’s “Thin red line of ‘eroes” when the drums begin to roll,

The drums begin to roll, my boys, the drums begin to roll,

O it’s “Thin red line of ‘eroes” when the drums begin to roll.

- Tommy, Rudyard Kipling

The other is an old saying from the folklore of the midwestern United States.

There’s only a thin red line between the sane and the mad.

Both of them suggest something of the meaning of Mallick’s film, the second no less than the first. The madness of war, into which we see our world so disastrously embroiled even as we write, is a central theme in The Thin Red Line. But it is not just about the graphic portrayal of action on the World War II battlefield of Guadalcanal Island. It is also about the interior wars within a war as the main protagonists try to cope with this madness.

Two of the chief protagonists in Malick’s The Thin Red Line are Private Witt (Jim Caviezel) and Sergeant Welsh (Sean Penn). Their dialogue with each other, as the skeptical Welsh tries to grapple with the reluctant but deep-thinking soldier, Witt, from beginning to redemptive end, are at the heart of Malick’s existential and spiritual vision of humanity.

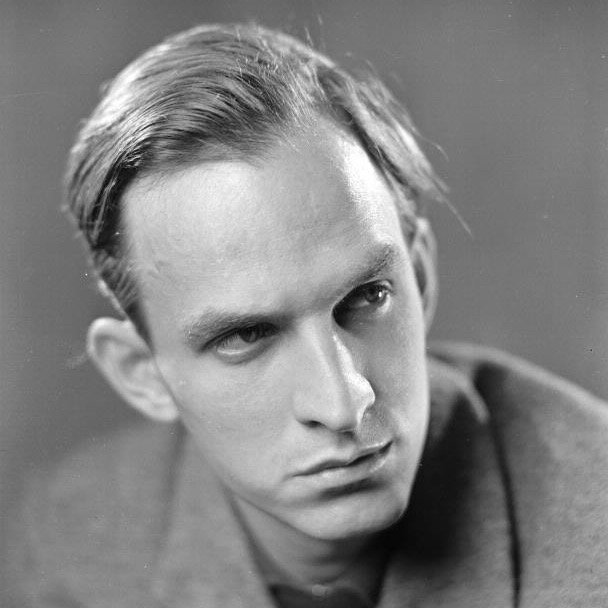

Malick doesn’t talk publicly about his work. He doesn’t give interviews and he doesn’t do press conferences. But what he does do is talk to his actors and producers. Not only does he talk to them but he forms them and collaborates with them in creating the magnificent legacy of philosophy and cinematic art he is leaving us.

At the stage of his career by which he had produced his five masterpieces, Badlands, Days of Heaven, The Thin Red Line, The Tree of Life and To The Wonder, Faber and Faber published a book entitled Terrence Malick – Rehearsing the Unexpected. It was edited by Carlo Hintermann and Daniele Villa and consists of over 300 pages of reflective comments from multiple people who worked with Malick on all those films. In many ways it gives far more insight to the artist than you would ever get in press conferences or interviews with the man himself.

In everything they say you can see not only the artist, his vision and how it evolves, even on the set. You also see the profound influence, subtle but gentle, which he has on all those who work with him and how he draws out of them a powerful collaborative role in giving us the final product.

Jim Caviezel, speaking about the audition process in which he was selected for The Thin Red Line, his first (major) acting role, reflects something of this relationship.

It was a revelation to me, because I was a basketball player and all I ever wanted to do was play in the NBA. But I wasn’t given the gifts, I had to work very hard for what I have. I just took that work ethic and I applied it toward acting and that voice that was calling me to get into the acting profession led me eventually to this moment in time, to do this movie. When I met with Terry, I think he knew I felt uncomfortable because I had put myself out on a limb by giving his wife a rosary and I felt:

“Well, I just blew that audition.’

But he immediately tried to find a place where we both came from and made me feel comfortable around him. What impressed me about him, as I have gotten to know him, is that he has an extraordinary gift: Terry Malick has a mind that is extraordinary but he also has the gift of humility.

Caviezel went on to play Jesus to stunning and harrowing effect in Mel Gibson’s The Passion Of The Christ.

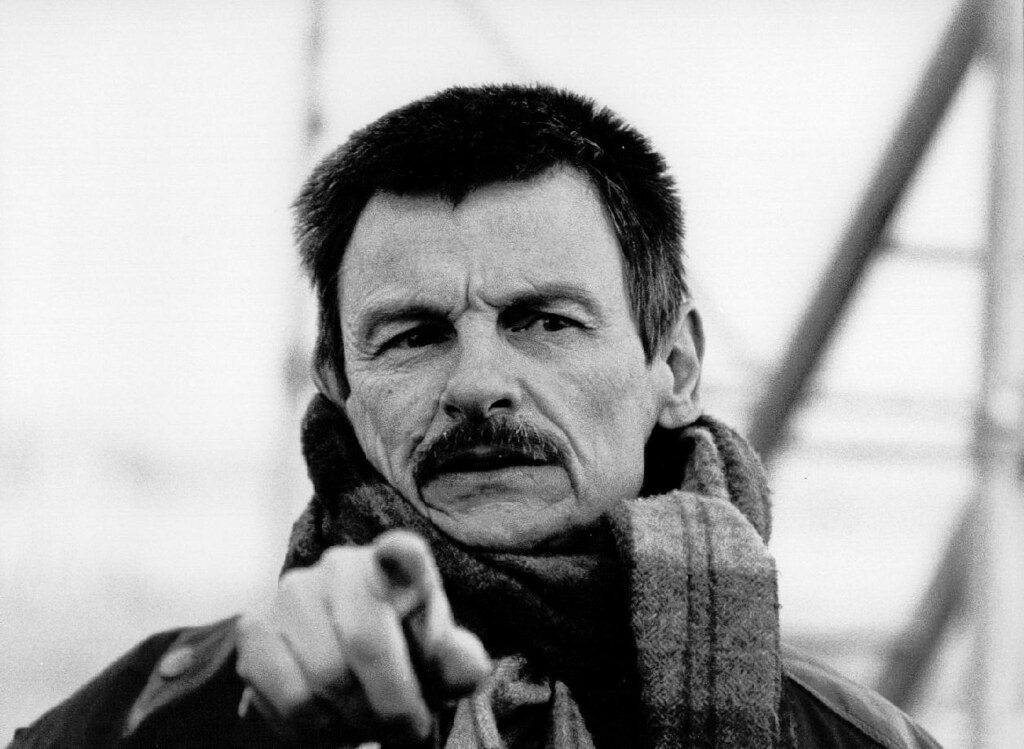

In casting Penn as the hard-nosed Sergeant Welsh it is clear that Malick knew his man.

Penn’s comment on working with Malick clearly shows the rather desperate vision he has of the battles we face in this world.

I haven’t met a non-desperate character on this earth, in some way … People are trying to balance their mortality, against their fears and their sense of themselves as men, as Americans – all of that stuff that’s dealt with in The Thin Red Line; all that balancing against the mysteries: ‘Is there somebody up there, is there not?’ And short of the knowledge of that, there’s some desperation. And war is as desperate as men can get.

Malick, as Penn saw him, was concerned with the way that we are innocent, concerned with the way that we’re damaged, with the way that we’re cruel, the way that we love – he’s concerned about all the things that represent our lives. And I do think that he is a real poet among academics. ‘Cause he’s both. He’s a very complicated guy.

Ben Chaplin, who plays the troubled Private Bell also perceived Malick’s deepest preoccupations.

In all Malick’s films there’s almost always this question about original sin.

Do we have this thing in-built, this ability, this desire to kill, to destroy what’s around us? How can we maintain an innocence?

To a certain degree, they are all about the loss of innocence. And that loss of innocence is inevitable as soon as a child learns to speak. It’s like the garden of Eden with the apple: if the apple’s there you are going to try it. I suppose that’s what his films share.

As in any war, death is always a presence. The conversations which Witt and Welsh have elicit this reflection from the private about death and immortality.

I remember my mother when she was dying.

Looked all shrunk up and grey. I asked her if she was afraid.

She just shook her head.

I was afraid to touch the death I seen in her.

I heard people talk about immortality, but I ain’t seen it.

I wondered how it’d be when I died.

What it’d be like to know that this breath now

was the last one you was ever gonna draw.

I just hope I can meet it the same way she did.

With the same … calm.

Cos that’s where it’s hidden – the immortality I hadn’t seen.

He reflected further that many times in our lives we are all afraid of death and most of us don’t want to talk about it, or be near it, but we are all going to end up there some day. He interpreted his character in the film as having a transformation in his soul after spending some time living with the natives on the island.

There, he said, Witt saw beauty, peace and love; he had received grace in his heart. And that grace equates with God and the grace filled him and made him. But he saw something greater in Heaven than he did on this earth, that there’s another life out there, that you can start living in heaven now, even in hell, and war. And that was a gift that was given to him and that grace keeps growing in him because he keeps finding ways to save men.

It’s easy to love people when they love you – but what if they hate you? Love your enemies … he concluded.

Mike Medavoy who played a central role in the production of The Thin Red Line said of it afterwards,

I found the film to be very poetic, very religious: you almost have a Christ figure giving up his life for everybody else, for the rest of the guys. I thought it captured World War II in that venue very well. And, well, for me that character is Terrence Malick.

Sean Penn summed it up this way: The importance of Malick is just showing that it’s okay to put a couple of thoughts into a picture… in a culture that doesn’t. I think it’s really simple: he’s an artist and we need art.