Do we live in the best of times or do we live in the worst of times?

Ross Douthat of the New York Times seems to think we stand somewhere in between and has been mulling over the direction in which we might be heading.

His mulling is mainly in an American context but his spectrum encompasses the wider Western world as well. Ireland, as an offshore island for the driving forces of corporate America, is certainly not difficult to include in his exploratory analysis of the watershed our western civilisation now seems to straddle.

In some recent writing – in his weekly NYT column and his newsletter for subscribers – he admits to no more than “dabbling” in a peculiar kind of optimism about the American future, arguing that if we can avoid various forms of self-destruction over the next decade or two, we might find ourselves in a better position than almost any peer or rival — as an ageing world’s last bastion of dynamism and growth.

But he admits that dynamism and growth are a far cry from what ultimately matters or what can give any guarantee of even a semblance of human happiness.

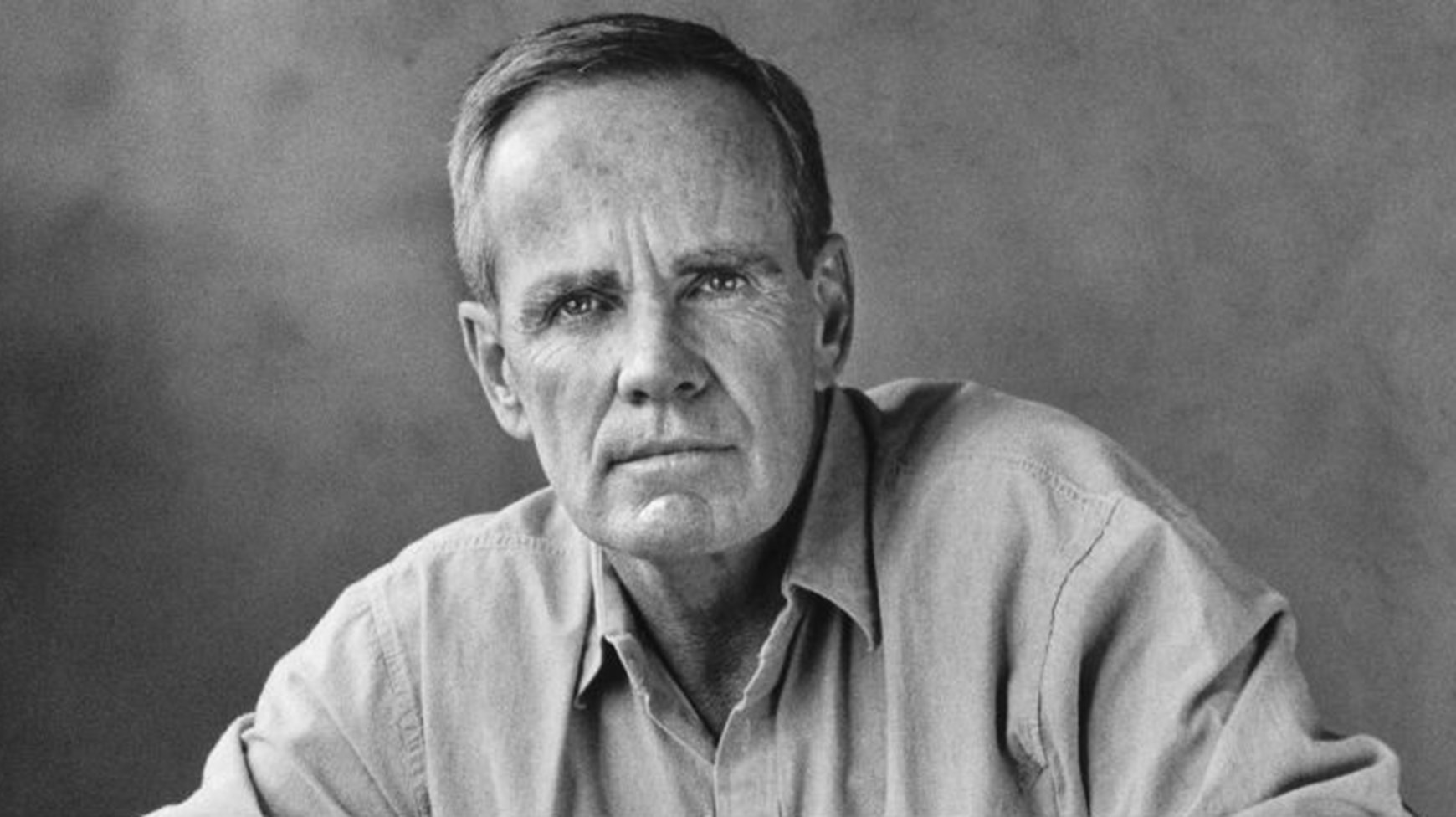

Rod Dreher is an apostle preaching a more pessimistic vision of the direction in which he sees us currently hurtling. He is proposing a more radical and demanding solution to a decaying world than Douthat: cut yourself off from all that corrupts you in modernity – because it is irredeemable. Abandon it.

No matter how comfortable and cultured we might feel in this present dispensation, Dreher argues that if the human spirit is denied what it takes to fulfil the deepest longings of the soul: a sense of cosmic purpose beyond mere individualism, and common values beyond the whims and aspirations of the self, it will remain lost in a wilderness.

Douthat is a more optimistic apostle. He seems to suggest that we have a different kind of choice. His optimism rests on his reading of the history of mankind, right back to the Garden of Eden. In a certain way the choice before us is the same fatal choice which confronted Adam and Eve. Do we make a pact with Satan, as they attempted to do, or do we draw all the benefits we can from the second chance given to us and them by the Creator after their Fall?

Douthat reminds us how the serpent gave Eve and Adam some sort of forbidden knowledge, “yes – but it’s before that Fall, not afterward, that God tells humanity to fill the Earth and subdue it, and when Adam and Eve are cast out of Eden that mission carries on, just freighted with more suffering and pain.”

The great temptation confronting the modern world, Douthat suggests, is the temptation succumbed to by the legendary Doctor Faustus, who made a pact with Mephistopheles to gain the whole world and lost his soul in the process.

Douthat identifies a line of tension that runs through a lot of his own writing.

I’m a Catholic writer who often criticizes the decadence of the late modern world and urges it to rediscover dynamism and ambition. But if techno-capitalist ambitions are fundamentally Faustian, should a Catholic observer (or anyone else with similar commitments) really wish for them to rise again? In the Bible, after all, Promethean dreams are not always treated kindly. It’s the serpent who promises forbidden knowledge, the bloody-handed Cain who founds the first city (Genesis 4:17-18), the builders of Babel who are scattered to the winds. Maybe the Promethean spirit in America needs to be exorcised, not revived.

Douthat is looking for a way in which serious conservative or convinced religious believers can welcome a new American century not defined by the spirit of the famous doctor, whose impulse was to bargain for power with the very devil?

Douthat gently takes issue with some who would consider Christianity to be a religion exclusively concerned with bearing suffering in the present for the sake of the hereafter. In fact, he says, the dynamism of Christian cultures has usually reflected the working-through of the tensions between that conception of the faith and the equally powerful conception of Christianity as a religion of repair, reform, healing even revolution. He sees in the fabric of both the Old and New Testaments a weaving of this tension reflecting both a fallen world to be patiently endured and a fertile world that can be mastered and transformed.

The first murderer builds the first metropolis, yes, but the history of God’s people centers on Jerusalem, the holy city; the Bible culminates in a transformed and redeemed cosmopolis, not a return to a purely pastoral Eden. God lets Israel suffer invasions because of its unfaithfulness, he scatters his chosen people and sends them into exile – but in the rare moments when the Israelites have faithful leaders, faithful kings, they prosper in worldly as well as supernatural terms.

He reminds us that Jesus treats suffering, his own and that of others, as part of God’s unfolding plan, a cup to be drunk deeply no matter how strong the urge to let it pass. But then he also heals the sick and suffering everywhere he goes, rewards people seeking healing who take extraordinary steps to reach him, and sends his disciples out to heal more people.

Then there is the history of the Christian Church and its interface with the world of human culture and development.

Followers of Christ went into the desert and lived on pillars and built monasteries and accepted violent death in every form. But they also built and developed and invented, forging the medieval and early modern forms of civilization that carried us forward into the scientific and industrial revolutions that made our own global civilization possible.

He does take note of a certain doom-laden Catholic account of this dynamic modern history (which tracks with certain doom-laden left-wing accounts of modern industrial capitalism) in which the last few hundred years of technological breakthroughs and rising life expectancies and soaring skyscrapers are just one long Faustian bargain, carrying us toward the same self-destructive endpoint as the architects of Babel.

He doesn’t think this account really works: “There has been so much growth and vitality for Christianity within the long era of scientific and technological progress, so many surprising rebirths for different forms of Christian faith, and an underappreciated relationship between dynamism in the secular order and revival in the religious realm that if you’re any kind of providentialist you have to see a version of technological modernity as part of God’s unfolding plan.” He cites Kendrick Oliver’s To Touch the Face of God, a study of “The Sacred, the Profane, and the American Space Program, 1957–1975”, affirming his view.

He is not saying that there isn’t also a version that tends to corruption, dehumanization and ultimately our destruction. He agrees with Dreher and other pessimists that you can see that darkness visible along some of the tech frontiers that our society is currently exploring, and in those futurist worldviews that imagine humanity superseded or replaced.

But in American history he sees plenty of evidence of ambitious, developmentalist, exploration-oriented visions which seek humane forms of economic growth, the wise use of new technologies, a moral discernment about scientific achievements but not the rejection of their fruits: “However attenuated and fragmented, those impulses still exist – more so, I would say, in our country than in any rival power or alternative cultural redoubt – and I think they still offer the best chance to battle the chronic illness of decadence without bargaining our humanity away.”

In the context of all this we might leave the last word to Romano Guardini, writing more than eighty years ago – in a book published in German just before the cataclysm of World War II. He was much preoccupied with the modern world and the advance of technology, both with the good in it and with those aspects which seemed to threaten our very humanity. He wrote:

One day the Antichrist will come: a human being who introduces an order of things in which rebellion against God will attain its ultimate power. He will be filled with enlightenment and strength. The ultimate aim of all aims will be to prove that existence without Christ is possible – no, that Christ is the enemy of existence, which can be fully realized only when all Christian values have been destroyed. His arguments will be so impressive, supported by means of such tremendous power – violent and diplomatic, material and intellectual – that to reject them will result in almost insurmountable scandal, and everyone whose eyes are not opened by grace will be lost.

When he wrote those words that Antichrist had already arrived on his continent in two incarnations, Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler. Both were defeated but their progenitor, Mephistopheles, is still as present as ever. Guardini assures us, in the depths of his Christian faith, that no matter how often he returns he will never prevail over those living in the grace of God, those to whom it will be clear what the Christian essence really is: that which stems not from the world, but from the heart of God; victory of grace over the world; redemption of the world, for her true essence is not to be found in herself, but in God, from whom she has received it. When God becomes all in all, the world will burst into flower.

The way of resistance to and correction of evil – implicitly Douthat’s way – seems to offer us a better future than the way of abandonment and flight from the world suggested by the pessimistic option. All time, in Guardini’s reading of our life in the world, is not of the world but “from the heart of God”. Therefore, we live in the best of times.

First published in the March edition of Position Papers Review